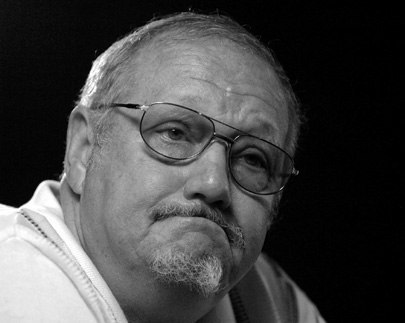

Jack Whittaker, a 55-year-old contractor from Scott Depot, W. Va., had worked his way up from backcountry poverty to build a water-and-sewer-pipe business that employed over 100 people. He was a millionaire several times over. But when he awoke at 5:45 a.m. on Christmas morning in 2002, everything he'd built in his life held only passing significance next to a scrap of paper in his worn leather wallet — a $1 Powerball lottery ticket bearing the numbers 5, 14, 16, 29, 53, and 7.

Whittaker had purchased his lucky ticket, along with two bacon-stuffed biscuits, at the C&L Super Serve convenience store in the town of Hurricane on Dec. 24, 2002. That night, Whittaker went to bed thinking he'd missed winning the lottery by one digit — only to wake up on Christmas Day to find that the number had been broadcast incorrectly and the winning ticket was in his hand. "I got sick at my stomach, and I just was [at] a loss for words and advice," he later remembered. When he returned to the convenience store on Monday, he quietly told the woman at the cash register he'd won. "No you didn't," she replied. "You're not excited enough to win the lottery."

The day after Christmas, Whittaker put on his Stetson cowboy hat, black suit, and white shirt — he always dressed this way — and appeared on live TV together with his wife Jewel, daughter Ginger, and 15-year-old granddaughter Brandi Bragg, to accept a check for $10 million from West Virginia Governor Bob Wise. It was the first portion of a jackpot that had been building since Halloween. On Christmas Eve, when he bought the ticket, the prize stood at $280 million. A late surge of buyers pushed it to $314.9 million, making Whittaker the winner of the biggest single undivided jackpot in lottery history.

"The very first thing I'm going to do is sit down and make out three checks to three pastors for 10 percent of this check," Whittaker announced in a half-hour press conference watched by many citizens of his state, which, along with 23 others (plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico) is part of the multistate Powerball lottery pool. He also said he planned to rehire 25 workers he'd laid off before Christmas and to fund schools and other programs to help West Virginians better themselves. "Seventeen million in the state of West Virginia will really do good for the poor," he said.

He also had his eye on a helicopter and wanted to send his wife Jewel on a trip to Israel. Bragg, his granddaughter, a beautiful girl with blonde hair, hazel eyes, and her grandfather's broad smile, said she wanted to meet the rap star Nelly and buy a custom blue Mitsubishi Eclipse.

Whittaker's good fortune was immediate and contagious. Larry Trogdon, who owned the C&L, got $100,000 from the lottery for selling the winning ticket. The state would receive approximately $11 million for school and senior-citizen programs from the 6.5 percent tax bite it levied on Whittaker's prize. Whittaker told the biscuit lady at the C&L to pick out a new Jeep, gave her a check for $44,000, and then bought her a house worth $123,000 more. He also made good on his promise to help the poor: He donated $7 million to build two new churches and set up the Jack Whittaker Foundation with an initial grant of $14 million for the purpose of aiding the needy. The Foundation gave money to improve a Little League park and buy playground equipment and coloring books for children. It was also able to help with some of the thousands of requests for aid of every kind that poured in from across the state.

Yet there was something about Whittaker's lottery winnings that felt different from the money he'd earned as a businessman. "I've had to work for everything in my life," he said at that first press conference. "This is the first thing that's ever been given to me."

The state announced Whittaker had won $314.9 million — it said so right on the giant check they gave him on TV — but Whittaker never saw anything near that amount of money. Instead of taking annual installments over 29 years, he chose a one-time payout of $113,386,407.77. After taxes, he was left with about $93 million, approximately 30 percent of the sum reported in the newspapers and advertised by Powerball. The false impression left by reports of Whittaker's record win was nevertheless a powerful lure for West Virginians to keep playing a lottery in which their chances of winning were negligible. (Where New York and Massachusetts, the two biggest lottery-playing states, take a mere 34 percent and 20 percent of the pot from their winners, West Virginia takes a full 41.5 percent.)

There is no shortage of lottery winners who go broke — enough to fill many seasons of reality television — but there was good reason to think that Whittaker, a successful businessman whose journey from rags to riches was the product of self-reliance and hard work, would make good use of his new wealth. The idea that 10 years later he would wish he'd torn up his winning ticket and thrown away the pieces would have struck the man and everyone who knew him as nuts.

Jack Whittaker's downfall began at the Pink Pony strip club in Cross Lanes, W. Va., a crenelated building with pink-frosted stucco walls and black glass doors. The club's unsettling combination of girlish innocence and highway-access-road menace might serve as a metaphor for the lottery winner's inner life. At approximately 5 a.m. on Aug. 5, 2003, Whittaker called the police from the parking lot of the Pink Pony complaining that he'd been drugged and that a substantial sum of money was missing from his Hummer. "There's no confusion on the fact that he didn't have all his faculties," a police spokesman told reporters. Whittaker gave the police a urine sample for analysis, and his private investigator found $545,000 in cash behind a trash bin an hour later; the strip club's manager and his girlfriend were charged with robbing Jack, but were never indicted. "I'm simply a businessman who has seen his share of failures and successes," Whittaker told reporters. "My personal life is my own, and I make no excuses for my actions."

Whittaker's faith that he could handle his enormous lottery winnings with the same qualities of self-reliance, hard work, and aggression that had allowed him to master previous challenges was tragically misplaced. Less than three months after the incident at the Pink Pony, Whittaker was arrested after driving his Hummer into a concrete median on the West Virginia Turnpike. The arresting officer, M.J. Pinardo, reported that he smelled alcohol, but Whittaker refused sobriety tests and became "extremely belligerent." The police found a small pistol and $117,000 in cash on Whittaker. "It doesn't bother me, because I can tell everyone to kiss off," he explained to reporters outside the local courthouse after his arrest. His reply to criticism of his gas-guzzling Hummer was equally succinct: "I won the lottery," he said. "I don't care what it costs."

The cost of Whittaker's insouciance went up sharply the following year. On Jan. 25, 2004, according to a police report, he got drunk, parked his car in the middle of the street, went away, returned to find that $100,000 he had left on the passenger seat was stolen, and was charged with drunken driving when the police arrived. Vernon Jackson Jr., also from Scott's Depot, was indicted on charges including breaking and entering an automobile and grand larceny, but it was also possible to imagine that Jackson had simply taken money Whittaker no longer wanted. After all, he'd left the cash out in plain sight on the passenger seat.

Later, Whittaker was arraigned on charges of trying to assault and threatening to kill Todd Parsons, the manager of Billy Sunday's Bar and Grill in St. Albans, after previously being banned from the establishment. Further lawsuits followed. In March 2004, Whittaker was sued by a floor attendant at the Tri-State Racetrack & Gaming Center in Nitro named Charity Fortner, who claimed he'd forced her head toward his pants while he gambled at the dog track. The suit was settled out of court for an undisclosed sum.

In September 2004 three men broke into Whittaker's home, even as a fourth man lay dead inside. The dead man, Jesse Joe Tribble, 18, had died of a drug overdose, though it was never exactly discovered when. The three burglars — J.C. Shaver, 20, James Travis Willis, 25, and Jeffrey Dustin Campbell, 20 — were captured on Whittaker's security cameras stealing stereo equipment and other valuables. (A wrongful death suit brought by Tribble's family against Whittaker was settled.) The four men were friends of Whittaker's granddaughter, whose spectacular public disintegration soon overshadowed that of Whittaker himself.

Whittaker's transformation from successful businessman and loving grandfather to disheveled and obnoxious strip-club patron took less than two years and alienated many of his friends and family members — beginning with his wife, who soon filed for divorce. While a reflection of Whittaker's own flaws, such personal upheaval is more common than not among jackpot winners, according to Mike Kosnitzky of Boies, Schiller & Flexner, a law firm in New York. Kosnitzky has been involved in the representation of half a dozen large lottery winners; his clients include a former attendant at a parking garage in Midtown Manhattan named Juan Rodriguez, who in 2004 won a Mega Millions jackpot worth $149 million.

In his experience, Kosnitzky says, most lottery winners suffer tremendous guilt as the result of their good fortune; they're also troubled by family members and friends who feel entitled to their winnings and who become angry when they don't get what they feel they deserve. Without access to financially and psychologically sophisticated advice, winners quickly find themselves easy marks for every kind of manipulation and often take refuge in preexisting addictions, which are compounded by seemingly inexhaustible wealth.

Contrasting lottery winners with professional athletes — who are often also from poor backgrounds, and suddenly find themselves blessed with great wealth — Kosnitzky says lottery winners generally do much worse. "With most athletes, there's enough attention on them from an early age that there's a vetting process before that circle is created," he said, pointing out that most professional athletes complete at least a year or two of college. "LeBron James has his friend Maverick [Carter], and they surrounded themselves with educated people who knew every aspect of law, finance, accounting, contract negotiations, and all the things he needed to know to build his brand. A lottery winner doesn't have that. It happens suddenly." Professional sports leagues, Kosnitzky says, are well aware of the perils of sudden wealth and prepare athletes accordingly, adding, "There's no rookie course for lottery winners."

Whittaker's combination of self-reliance, arrogance, and money were particularly dangerous for his granddaughter, a teenage girl whose father had committed suicide when she was small. Bragg's mother, Ginger, Whittaker's only child, had suffered from recurring lymphoma. As a result, the girl had lived off and on with her grandparents and became particularly close to her grandfather. When she got out of school, she telephoned the man she called Paw-Paw to tell him about her day; when she wasn't in school she often came with him to work. In their spare time, one friend told a reporter for the Washington Post, they liked to flop down on Bragg's bed together to watch movies and eat popcorn.

It was Whittaker's dream that Bragg would inherit everything he had amassed; he planned to give all of his companies and associated properties to her when she turned 21. "She was the shining star of my life, and she was what it was all about for me," he later said. "From the day she was born, it was all about providing and protecting and taking care of her."

Whittaker lavished her with money and gifts, including the pale-blue custom-painted Mitsubishi she had wanted and at least four other cars. According to her friends, it wasn't unusual for him to hand Bragg $5,000 in cash to spend in a single day, which didn't bring her happiness but an entourage of drug dealers and petty criminals. Within a year of Whittaker's windfall, Bragg went into rehab for OxyContin addiction, but she quickly relapsed. "They want her for her money and not for her good personality," Whittaker complained a year after his win to a reporter from the Associated Press. "She's the most bitter 16-year-old I know."

Surrounded by enablers and local kids who wanted to share in her wealth, Bragg dropped out of school and spent her days sleeping and shopping and her nights driving aimlessly and buying large quantities of junk food to keep her entourage fed. She also smoked "a lot of crack. Big rocks of crack," according to J.C. Shaver, one of the men who broke into Whittaker's house in September 2004. According to a reporter who peeked inside, the interior of Bragg's Mitsubishi was littered with candy wrappers, soda bottles, DVDs, and loose 5-, 10-, and 20-dollar bills — the change from the stacks of hundreds Whittaker gave her as spending money. Hundred-dollar bills would fly around inside the car and sometimes out the window as she cruised around with friends, one of them recalled. "She doesn't want to be in charge of the money. She doesn't want to inherit the money. She just looks for her next drugs," Whittaker told a reporter in 2004.

He had plenty of problems of his own. At one point, Whittaker estimated that he'd been involved in 460 legal actions since winning the lottery — an estimate quickly superseded by further arrests, along with more lawsuits, some of which were thinly veiled attempts at extortion. His attempts to recover money he'd loaned to friends and acquaintances were often expensive and usually in vain. He was sued by a casino for debts totaling more than $1 million; in a countersuit, Whittaker claimed the casino owed him money — for a new kind of slot machine he'd invented, which they'd promised to buy. In the hope of keeping trouble away, Whittaker hired off-duty sheriffs' deputies to guard his house and serve as bodyguards. The move appears to have discouraged law enforcement from pursuing drunk driving cases. It also reinforced his belief that his lottery wealth had put him beyond the reach of the law.

On Dec. 9, 2004, Whittaker decided to stop fighting a drunk driving charge in court, surrendered his driver's license, and checked himself into rehab. He also called the police to report that Bragg, now 17, had been missing since Dec. 4.

On Dec. 20 a girl's body was found wrapped in a plastic tarp behind a junked van in Scary Creek, an unincorporated area outside the town of St. Albans. The girl's body was in bad enough shape that police needed to use tattoos on the corpse to formally identify her as Bragg. Bragg had pills and a syringe hidden in her bra and cocaine and methadone in her system at the time of her death, which was ruled to be the result of an accidental overdose. Services were held Christmas Eve at the Ronald Meadows Funeral Parlors in Hinton. Jack and Jewel Whittaker sat side by side in a packed funeral home listening to a song by the rapper Nelly. White doves were released at Bragg's graveside.

Things didn't get much better for Whittaker after Bragg's death. In April 2008 his divorce from Jewel was finalized, ending nearly 42 years of marriage. In July of the following year, his daughter Ginger Whittaker Bragg was found dead in her opulent home on Lake Drive in Daniels. She was 42 years old.

On Jan. 25, 2008, Jack Whittaker once again bought a lottery ticket at the C&L convenience store in Hurricane. Lottery spokeswoman Nancy Bulla stated that Whittaker had "matched four numbers plus the Powerball number for a $10,000 prize" — meaning he had been one number off from winning a second mega-million-dollar jackpot. His run of bad luck had not yet ended.

In the ten years since he became the wealthiest lottery winner in history, Whittaker has spoken rarely with the press. There have been reports that he's broke. His name isn't listed in the phone book, and none of his businesses — which include a bewildering variety of names and addresses — seem to be currently operating. At the rural address on the tax returns of the Jack Whittaker Foundation, there's little more than a muddy lot with a few trailers and rows of used construction equipment. At the end of the lot, a small single-story building with a sign on the door reads "Please ring bell for assistance."

In October, I rang the bell and waited in the rain. Through the glass of the door, I could see a photocopied color snapshot of a smiling blonde girl with hazel eyes, whom I recognized as Bragg. The plant by the front desk was dead, and judging by the leaves on the carpet, had been for a while. Around back a man in work clothes was sitting in his Jeep, waiting for the tank to fill up with diesel. "You won't find him here," he said. He offered a rough location for another Whittaker office, half an hour away.

There, opposite a tractor dealership, was a modest house that served as an office. On the license plate of a gold Hummer in the driveway was a picture of a smiling Bragg. I left a note under the door and another note on the windshield of the Hummer.

When I came back the next morning the Hummer was gone. I knocked on the door. Whittaker's secretary was there and let me wait in a set of rooms with a space heater. After half an hour I got back in the car and headed north. Five minutes later, I passed a gold Hummer heading south, with Whittaker behind the wheel. I followed him at high speeds down a two-lane road for a while, until he doubled back toward the house.

I parked by the side of the road and walked up to the door of the house. Whittaker was standing outside by his mailbox and talking with a bearded man in a pickup truck. I nodded, giving him time to finish his conversation, and went inside to wait. Whittaker came in 10 minutes later with the man, whom he introduced as his pastor.

Dressed in his usual black suit, white shirt, and black Stetson hat, his barrel chest protruding over a sizable gut, Whittaker looked like a man who had done battle with the devil in a backwoods ghost story. "Today is my birthday — I'm 65 years old," he said, and then explained his policy of not giving interviews, except for money. I suggested that he'd been through experiences that no sane man would want to go through, that others might benefit from being able to understand, and that was why he should speak to me for free. I told him that his story was an American story, about the belief in luck and the damage people can do while meaning to do good.

He looked me up and down and shrugged. "I don't care what people think I am. That doesn't bother me one bit," he said. "I know who Jack Whittaker is. And some days I don't like who I am." He knew Christmas would be the 10th anniversary of his big win, a thought that seemed to fill him with pride and bitterness. "Yeah, I'm not even the biggest single winner anymore," he said. "Somebody about a month ago won $327 million somewhere, so that kicks me out of the Guinness Book of World Records." The charge for an interview would be $15,000. Otherwise, he said, he wasn't interested in talking.

He kept talking anyway. He hardly needed the money, he explained; reports that he was broke were false. His refusal to give interviews wasn't the result of shame, but rather his response to the lies that have been printed about him and broadcast on TV. "That's the only way that I can live with the way they print things, and if I'm getting paid, they can write whatever they want to about me," he said. "I'll be their whore, I don't care."

He gestured over to a stack of papers on top of a file cabinet. "I got a stack of screenplays this big that people are offering to me about my life, and they all have something wrong with them," he said. "They don't have what's right."

His pastor smiled. Whittaker had built his church and funded his missions to Africa. They went hunting together. He knew that there was good and bad in Whittaker, just as there was good and bad in everyone. "Somebody needs to take it back to the beginning, the old sawmill days, when there was nothing there," he offered. "When you and your dad and them, they built that Mary Jane Church."

"You were a millionaire before you won the lottery, right?" I asked him.

"Nobody knew I had any money," Whittaker said. "All they knew was my good works."

"Life was easier then too, wasn't it," the pastor said, in the instructive tone of voice one might use with a bright but headstrong child.

"Yeah, it was a lot easier then," Whittaker said sadly.

(Click to display full-size in gallery)

(Click to display full-size in gallery)

Thanks to lottaballz and Evan for the tip.

Ding Cuckoo!

Won't see me crying for him, he brought this upon himself.

Moral of the story is, 'Don't be so darn boastful and careless after winning, it will always come back to bite you in the ass!'

That's what makes this whole story sad...this was a business man, a man who already had money,

a person who worked his way from the ground up. you'd think things would have worked out better for

him than the average joe lottery winner.

The old adage is true " Money, especially vast sums of money reveals who people truly are"

Lottery winners have lost close friends over money.At times so called friend or acquaintances seems to think that if one of them wins, they all entitled to partake of the winnings, when that is rejected- the hatred comes out.

Life tells us that we ought to learn lessons from those who went before- but for some reason there are those people who want to experience it for themselves.

Pain....you gotta love it.

Nice Story,

Losing Ticket huh, .... Sure makes You Think

He should have just bought the sandwich.

I wonder how he feels about killing his family members??

Jack Whittaker is my Whore............

If any members of Lottery Post win the jackpot,Todd would like a new Corvette.

lol. lol. I think we can be quite certain that post was NOT endorsed by Todd...... lol.lol.

I would anyone here should be happy to give him the exclusive story.

(except for those who will go into remote seclusion, of course)

If JW is looking for a screenwriter for his life story, he needs to hire the writer of this article.

The surprising thing about Whittaker's crash and burn is that he was already a self made millionaire.

One would think that he would be better at managing money, unlike say, David Edwards who was a failure to begin with.

The stupidest part is carrying gobs of cash around,

my guess is people

like Bill Gates, Warren Buffet and even Jimmy Buffet don't even have $100.00 in their pocket.

The saddest part is the grand-daughter, 4 cars, really ? $ 5000.00 cash spending $ for 1 day, really ?

You give a teenager money like that and with limited things to do in a small town and likely little interest in school and no adult monitoring, you are asking for trouble,